THE HUT TAX WAR OF 1898: A Battle of Rights

Did you know that the Hut Tax War of 1898 arose from a resistance to a new tax imposed by the colonial governor in the newly annexed Protectorate of Sierra Leone established by the British to demonstrate their dominion over the territory following the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885?

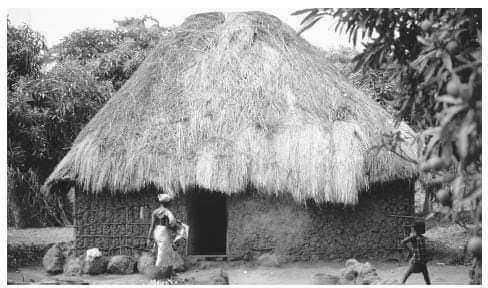

The governor of Sierra Leone, Colonel Frederic Cardew, had decreed that to pay for the British administration, the Protectorate's residents had to pay a tax based on the size of their huts. Cardew, who was not an administrator but a professional soldier with service in India and South Africa, revealed his ignorance of the lives of most residents by the severity of the tax.

The owner of a four-roomed hut was to be taxed ten shillings a year; those with smaller huts would pay five shillings. Cardew's staff failed to advise him that the taxes, first imposed on 1 January 1898, often were higher than the value of the dwellings. In addition, the government taxed unoccupied dwellings.

Lastly, Cardew's demands that the chiefs organize their own residents to maintain the roads ignored the fact that the people needed to devote their labour to subsistence farming in order to survive.

A total of 24 chiefs signed a petition to the colonial government explaining why these requirements were so burdensome and threatened their societies, to no avail. In addition, the chiefs believed the tax was an attack on their sovereignty.

The new requirements sparked two rebellions in the hinterland of Sierra Leone in 1898, one in the northern area of the Temne, led by Bai Bureh, a general and military strategist, and the other in the southern area by the Mende, led by Momoh Jah.

The British issued a warrant to arrest Bai Bureh, the 61-year-old chief of the Temne, with the idea that a display of force would convince the natives to pay the taxes due. By February this had provoked open warfare, with resistance spreading. But Bai Bureh continued to make peace overtures in April and June, including through the mediation of Limba chief Alamy Suluku of Bumban, which Cardew rejected, saying that the general had to surrender without condition.

Bai Bureh had gained the support of several prominent native chiefs, including the powerful Kissi chief Kai Londo and the Limba chief Suluku. Both chiefs sent warriors and weapons to aid Bai Bureh, who felt he had to defend himself against the aggression of district commissioner Captain Sharpe.

Bureh's fighters had the advantage over the better armed British for several months of the war, with high casualties on both sides. Some innocent European and Africans were also killed. In one case, Johnny Taylor, a Creole trader, was "chopped" to pieces by Bai Bureh's warriors.

As frustration grew, Governor Cardew realized that the war was not easily winnable so he ordered a "scorched earth policy" where the British would burn entire villages, farmlands, and pastures. This change in tactics significantly affected Bai Bureh's war effort, as it reduced provisions to feed not only his warriors but his subjects as well. He also realized that the cost of reparations was getting insurmountable as the British were relentless in pursuing the new policy.

To save his people from more property losses, Bai Bureh finally gave up the fight, surrendering on 11 November 1898. Despite the British government's recommendation of leniency, the acting governor had Bai Bureh and two colleagues sent into exile in the Gold Coast (now Ghana). The British convicted and hanged 96 of his comrades. Bai Bureh was allowed to return in 1905, when he reassumed chieftaincy of Kasseh. Bai Bureh gave an account of his side to Rev. Allen Elba, who sent an account to Cardew, although historians have ignored this material.

The Southern front was based in the Southern provinces, and was led mainly by Mende (and a few Sherbro) warriors and chiefs. In this area, the warriors killed many Creole and civil servants living in the provinces. Lieutenant Colonel Marshall, the British commander, wrote that the operations, from February to November 1898, involved some of the most stubborn fighting that has been seen in West Africa. No such continuity of opposition had at any previous time been experienced on this part of the coast.

For the British, this had been one of the larger West African colonial campaigns of the nineteenth century. Apart from support units and a 280 strong naval brigade, British–led forces consisted of West India Regiment and African troops led by British officers, including the West Africa Regiment, Sierra Leone Police and local levies. These forces together suffered 67 killed and 184 wounded, in addition to the death of 90 non-combatant carriers, plus losses among the local levies which were not recorded.

The defeat in the Hut Tax War ended large-scale organised armed opposition to colonialism in Sierra Leone. But resistance and opposition took other forms, particularly intermittent, wide-scale rioting and chaotic labour disturbances. Riots in 1955 and 1956 involved "many tens of thousands" of natives in the protectorate.

Source: Wikipedia

#penglobalhistory