CETSHWAYO: The Succession Story and Battles of the Last Great King of the Zulu Kingdom

Did you know that Cetshwayo, the last great king of the Zulu Kingdom, reigned from 1873 to 1879 and was the Zulu leader during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 against the British?

Cetshwayo (Cetewayo), the son of Zulu King Mpande and Queen Ngqumbazi (half-nephew of Zulu King Shaka and grandson of King Senzangakhona), in order to secure his rights to the throne of his father, defeated and killed in battle his younger brother Mbuyazi, Mpande's favourite, at the Battle of Ndondakusuka in 1856. Almost all Mbuyazi's followers were massacred in the aftermath of the battle, including five of Cetshwayo's brothers.

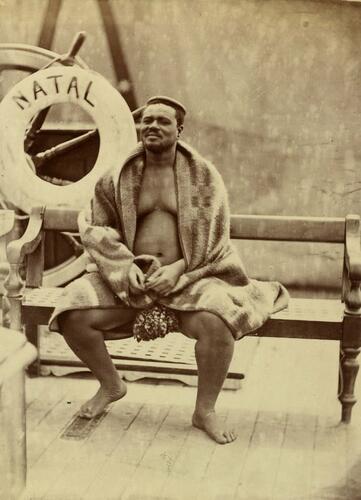

Following this he became the ruler of the Zulu people in everything but name. He did not ascend to the throne, however, as his father was still alive. Regarding his huge size, it was said that he stood at least between 6 ft 6 in (198 cm) and 6 ft 8 in (203 cm) in height and weighed close to 25 stone (350 lb; 160 kg). His other brother, Umthonga, was still a potential rival.

Cetshwayo, continuing the seige, also kept an eye on his father's new wives and children for potential rivals, ordering the death of his favourite wife Nomantshali and her children in 1861. Though two sons escaped, the youngest was murdered in front of the king. After these events Umthonga fled, twice, to the Boers' side of the border in 1856, apparently making Cetshwayo believe that Umthonga would organize help from the Boers against him, the same way his father had overthrown his predecessor, Dingane. He also had another rival half-brother, named uHamu kaNzibe, who betrayed the Zulu cause on numerous occasions.

Mpande died in 1872. His death was concealed at first, to ensure a smooth transition. Cetshwayo was installed as king on 1 September 1873. Sir Theophilus Shepstone, who annexed the Transvaal to the Cape Colony, crowned Cetshwayo, but turned on the Zulus as he felt he was undermined by the king's skillful negotiations for land area compromised by encroaching Boers and the fact that the Boundary Commission established to examine the ownership of the land in question actually ruled in favour of the Zulus. As was customary, Cetshwayo established a new capital for the nation and called it Ulundi (the high place), as well as expanded his army.

In 1878, Sir Henry Bartle Frere, British High Commissioner for the Cape Colony, sought to confederate the colony the same way Canada had been, and felt that this could not be done while there was a powerful Zulu state bordering it. Frere thus began to demand reparations for Zulu border infractions and ordered his subordinates to send messages complaining about Cetshwayo's policies, seeking to provoke the Zulu king. They carried out their orders, but Cetshwayo kept calm, considering the British to be his friends and being aware of the power of the British Army. He did, however, state that he and Frere were equals and since he did not complain about how Frere administered the Cape Colony, the same courtesy should be observed by Frere in regards to Zululand.

Eventually, Frere issued an ultimatum that demanded that Cetshwayo de facto disband his army. His refusal led to war in 1879, though he continually sought to make peace after the Battle of Isandlwana, the first engagement of the war. After an initial decisive but costly Zulu victory over the British at Isandlwana, the British retreated, with other columns suffering two further defeats to Zulu armies in the field at the Battle of Intombe and the Battle of Hlobane. While this retreat presented an opportunity for a Zulu counter-attack deep into Natal, Cetshwayo refused to mount such an attack, his intention being to repulse the British offensive and secure a peace treaty. However Cetshwayo's translator, a Dutch trader he had imprisoned at the start of the war named Cornelius Vijn, gave warnings to Chelmsford of gathering Zulu forces during these negotiations.

The British then returned to Zululand with a far larger and better armed force, finally capturing the Zulu capital at the Battle of Ulundi, in which the British, having learned their lesson from their defeat at Isandlwana, set up a hollow square on the open plain, armed with cannons and Gatling guns. The battle lasted approximately 45 minutes before the British ordered their cavalry to charge the Zulus, which routed them. After Ulundi was taken and burnt on 4 July, Cetshwayo was deposed and exiled, first to Cape Town, and then to London. He returned to Zululand in 1883 after his cause had been taken up in 1881 by, among others, Lady Florence Dixie, correspondent of The Morning Post, who wrote articles and books in his support.

Prior to his return, by 1882, differences between two Zulu factions—pro-Cetshwayo uSuthus and three rival chiefs led by Zibhebhu—had erupted into a blood feud and civil war. In 1883, the British government tried to restore Cetshwayo to rule at least part of his previous territory but the attempt failed. With the aid of Boer mercenaries, Chief Zibhebhu started a war contesting the succession and on 22 July 1883 he attacked Cetshwayo's new kraal in Ulundi. Cetshwayo was wounded but escaped to the forest at Nkandla. After pleas from the Resident Commissioner, Sir Melmoth Osborne, Cetshwayo moved to Eshowe, where he died a few months later on 8 February 1884, aged 57–60.

His body was buried in a field within sight of the forest, to the south near Nkunzane River. The remains of the wagon which carried his corpse to the site were placed on the grave, and may be seen at Ondini Museum, near Ulundi. Cetshwayo's most prominent role in South African historiography is being the last king of the Zulu Kingdom. His son Dinuzulu, as heir to the throne, was proclaimed king on 20 May 1884, supported by (other) Boer mercenaries.

Source: Wikipedia | Image: Brittanica

#penglobalhistory ##Cetshwayo