CRANIOPAGUS PARASITICUS: The Two-Headed Boy of Bengal, Manar and Islaam, and Other Parasitic Twin

Did you know that there have been at least 80 known cases of craniopagus parasiticus (parasitic twin), and that only 10 cases of have been documented in the medical research literature?

Craniopagus parasiticus is an extremely rare type of parasitic twinning occurring in about 2 to 3 of 5,000,000 births. In craniopagus parasiticus, a parasitic twin head with an undeveloped body is attached to the head of a developed twin. There have been at least eighty known cases of craniopagus parasiticus. Only ten cases of craniopagus have been documented in the medical research literature.

Few individuals survive until birth. For those who do, the only treatment available is to surgically remove the parasitic twin. Of the two documented attempts, however, one child died within hours and neither reached their second birthday. The problem with surgical intervention is that the arterial supplies of the head are so intertwined that it is very hard to control the bleeding, but it has been suggested that cutting off the parasitic twin's arterial supply might improve the odds of the developed twin's survival.

The exact development of craniopagus parasiticus is not well known. However, it is known that the underdeveloped twin is a parasitic twin. Parasitic twins are known to occur in utero when monozygotic twins start to develop as an embryo, but the embryo fails to completely split. When this happens, one embryo will dominate development, while the other's development is severely altered. The key difference between a parasitic twin and conjoined twins is that in parasitic twins, one twin, the parasite, stops development during gestation, whereas the other twin, the autosite, develops completely.

In normal monozygotic twin development, one egg is fertilized by a single sperm. The egg will then completely split into two, normally at the two-cell stage. If the egg splits in the early blastocyst stage, two inner cell masses will be present, eventually leading to the twins sharing the same chorion and placenta, but with separate amnions. However, the egg can split into two, but still have one blastocyst. This will lead to one inner cell mass and one blastocyst. Then, as the twins develop, they will share the same placenta, chorion, and amnion. This is thought to be the most likely reason why conjoined twins occur, and could possibly play a role in the development of craniopagus parasiticus.

One hypothesis is that craniopagus parasiticus starts with the development of two fetuses from a single zygote that fail to separate at the head region around the second week of gestation. Another is that it occurs later in development, around the fourth week of gestation, at which time the two embryos fuse together near the anterior open neuropore. A third hypothesis is that there is joining of the somatic and placental vascular system of the twins, as well as a degeneration of the umbilical cord of the parasitic twin. This suggests that craniopagus parasiticus develops due to the lack of blood supply to one of the twins.

Fewer than a dozen cases of this type of conjoined twin have been documented in literature. Only four cases have been documented by modern medicine to have survived birth.

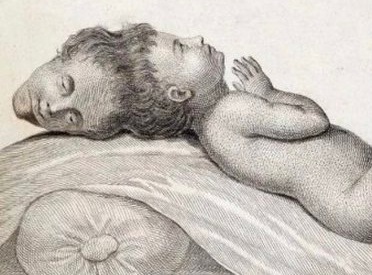

The first case on record is that of the so-called "Two-Headed Boy of Bengal", who was born in 1783 at the village of Mandal Ghat in the New Jalpaiguri district of the Indian state of West Bengal and died of a cobra bite in 1787. His skull remains in the collection of the University of Glasgow Hunterian.

On December 10, 2003, Rebeca Martínez was born in the Dominican Republic. She was the first baby born with the condition to undergo an operation to remove the second head. She died on February 7, 2004, after an 11-hour operation.

On March 30, 2004, Manar Maged was born. On February 19, 2005, 10-month-old Manar underwent a successful 13-hour surgery in Egypt. The underdeveloped conjoined twin, Islaam, was attached to Manar's head and was facing upward. Islaam could blink and even smile, but doctors determined she had to be removed, and that she could not survive on her own. Manar was featured on an episode of The Oprah Winfrey Show and in the British documentary series Body Shock. Manar died on March 26, 2006, fourteen months after the surgery, just days before her second birthday, due to a severe infection in her brain.

On January 20, 2021, a baby was born at the Elias Hospital in Bucharest, Romania, but died some hours after being born.

Source: Wikipedia

_1755775186.jpg)